« Wait, you’re walking all the way to Rome?! »

« Do you really wear those clothes all the time? »

« Are you sleeping outside? Where do you stay?

« That cell phone isn’t very historically accurate… »

Many people ask us questions like these, and I think they’re entirely reasonable. Therefore this post is not about accommodations as in lodging, but about the systemic compromises & differences we noted between our modern pilgrimage and equivalent historical journeys.

Modern things we enjoy as pilgrims

A) Individual safety (eg. No violence/hate on basis of dress/creed)

Our historic attire attracts attention, but rarely judgement and we are rarely at risk of violence or discrimination on the basis of our dress. This stands in sharp contrast to nationalist prejudices even just a century prior, where provincial attire or dialects were seen as at best exotic, and more typically as backward. (See ‘Vergonha’ wiki)

We joke that Esther is Protestant (ooga booga booga!) abroad in very traditionally Catholic countries, but this functionally makes zero difference and has never barred us from hostels or churches. The only religious observance we have had to follow sometimes has been sleeping in separate beds. And that’s more about mattress size than sex or spirituality. But overall, secular ecumenicalism is something radically new in the longer history of European religious history.

Our only unnerving moment in any of our lodging came when our door was opened inadvertently by the pressurized air conditioning changing in the hallway of one Swiss hotel. We barricaded it closed for peace of mind, and slept well after (see photo below).

Drunk men have given us annoyance repeatedly, but never in a serious way. As we’ve said before, costume doesn’t imply consent!

We have occasionally encountered regional political protests, but have never felt unwelcome or judged for being American or foreign. I’m Jewish by heritage, and have never felt discriminated against for this while abroad Nothing about our appearance is overtly political, but given the far right cooption of “heritage” in dress and rhetoric we still make the point that we are neither royalists nor fascists.

We have met armed soldiers and police throughout our trip, but have not been subject to any kind of coercion beyond basic security checkpoints at borders. And in those instances it’s mostly a question surrounding the unfamiliarity of our layered dress, and making sure we aren’t hiding contraband cheeses down our body linens.

Some of our family expressed concern about our journey, based on the coverage of urban protest and “migrant crime” in conservative Western media. But the ultimate irony about this is that each European country we passed through has had far better standards and access to maternal health, parental leave, contraception, health care etc, than we do in the US.

Conclusions on A) Individual safety: Our historic dress mostly stands out as cheerfully quirky and apolitical. It helps greatly that we present as a cis-hetero couple, and aren’t visibly a religious minority – though some people ask us if we are Amish or religious evangelists!

B) Technological certainty (eg. Digital maps, accurate meteorology)

Thanks to GoogleMaps and the equivalent Via Francigena digital app, we always know where we are, down to the exact location.

Thanks to modern meteorology, we know exactly what weather to expect, and therefore how to dress and prepare our gear accordingly.

Thanks to instantaneous digital communication, we can anticipate conditions on the ground days or weeks ahead, and plan ahead.

Conclusions on b) technological certainty: Most risk in historical travel came from exposure to natural elements that were outside of human prediction. While we have dodged some extreme weather (like nearby flooding in eastern Switzerland), our trip has been remarkably sheltered. Our only complaint perhaps is that Saint Bernard dogs *didn’t* need to rescue us crossing over the Alps!!

C) Technological Creature Comforts

Perhaps this goes without saying, but the modern world is a miracle that most people take entirely too much for granted .

Microwaves and washing machines eliminate much domestic drudgery for us, which was moreover historically very gendered.

Even 10 years ago we would have needed vocab phrase books and dictionaries to communicate- now Google Translate allows us to speak with strangers effortlessly, and even to translate via photos!

Food is abundant nearly everywhere we visit, and our only risk really is gaining weight (or getting sick from food left in our bags).

We have contacts to correct our vision, electrolytes to balance our metabolism, and there is always the failsafe of motorized help.

Conclusions on C) All these ‘basics’ of modern life are something we keenly appreciate, not just after a long day of walking, but because of more primitive historical conditions that we’ve experienced at immersion events. We are hardly “roughing it”, even though ubiquitous air conditioning appears to be uniquely American.

D) Gender equality? (eg. Less risk of sexual violence/casual assault)

50 years ago Esther could not have had her own credit card.

50 years ago, lodgings would have required we be married to book.

50 years ago, neither marital rape nor sex harassment were crimes.

We have met some remarkable female pilgrims travelling entirely alone. 50 years ago, this would have been extremely unlikely/unsafe.

[Nb. Each EU state varies in how they collect data on sexual violence. So there’s no uniform data set, particularly when assault typically goes unreported. But the fact such data is collected is itself key.]

Conclusion on D) We wouldn’t call this gender equality: women on pilgrimage still have to take measures to guarantee their safety and wellbeing while traveling which men don’t. However, the fact that women can safely undertake this trek and expect safety to be the norm is really great.

E) Certainty/privilege (eg. Credit card, international flight)

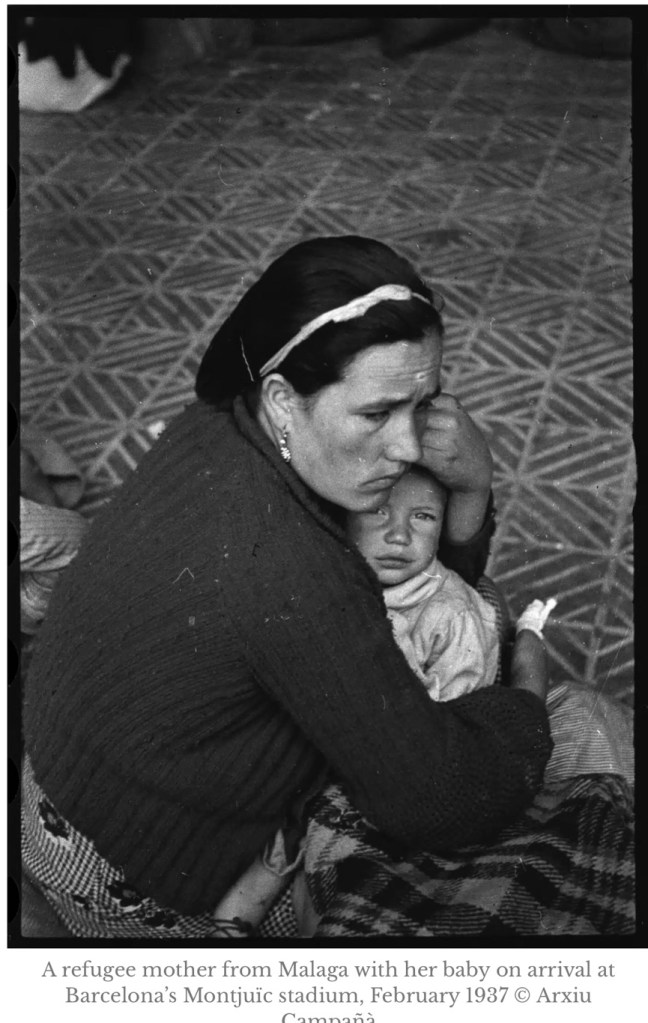

Ultimately, the real privilege and contrast in our trip to history is that it’s our choice. We are not escaping justice. We are not undergoing penance. We are not fleeing conflict. True, we are more reliant on the grace of strangers than ever before, but there are nearly always “ways out”. And this is a luxury that isn’t true for much of human history, and still isn’t the case in most international settings today.

Historical amenities we LACK today as modern pilgrims

With all of the above in mind, we have realized some broader realities that were present in past pilgrimages, or rather historical norms or systems which we struggle without in our current journey.

A) Vague (weather dependent) Scheduling

Basically, we can’t “wing it” at all on our trip, as past pilgrims could.

Our biggest constraint logistically is the Schengen Zone 90 day tourist visa for Americans. We cannot hide our non resident status, which is checked every time we book commercial lodging. Meanwhile, 18th century pilgrims did not have legal ID, much less biometric data!

Digitally pre booked accommodations also have changed the nature of pilgrimage. The internet has revolutionized access to lodging, but very little of it now is spontaneous. Even in the 1990s this was very different, and while this was likely more chaotic, it seemingly gave pilgrims more leeway and flexibility in choosing places to stay.

B) « Désertification’ of rural life

This is perhaps the most keenly felt for us- the withering up of rural society in Europe (and within the post-industrial West generally).

For much of our time in France, there were very few grocery stores or independent stores selling food at all. Outside of big cities, the landscape is all mechanized, monoculture, and highly intensive farming. The result is a remarkable surplus of cheap calories, but the absolute destruction of traditional rural village life and economies.

Basically, even if we found a barn to sleep in, like historic pilgrims, it’d be too full of pesticide residue or factory farmed animals to safely stay in. If we slept rough we’d likely be moved along by police or landowners as vagrants. We cannot stay in churches, and without a car, there are sharply limited services available in rural areas.

C) Animal driven human-scaled infrastructure

The roads of the past were based on the scale of humans and animals. Today, they are built for efficient motor transport. The result is that pilgrims in foot are often totally exposed to danger on busy highways which cannot be bypassed, particularly in mountains.

And while I do not mourn the lack of dirt roads and manure, statistically, the most dangerous thing we encounter every day on our journey is cars. To counter this, we are often forced onto the literal margins, or must default to bushwacking or public transport.

D) Community & comraderie

Up until Tuscany, the most popular part of the Via Francigena, we met only a handful of pilgrims. We understand that pilgrimage, particularly for an extended journey like ours, is a privilege. But we certainly mourn both the safety and community of having other travelers like ourselves to share the challenges of the road with us.

E) Freedom from capitalism

Most of all, we mourn the reality that nearly all our friends and family cannot take part in our journey, even for limited periods of time, even when we volunteered to pay for the cost of travel to and from Europe. This inability is entirely due to modern costs of living.

Historical pilgrims did not have mortgages, student debt, or 9-5s to legally answer for. The relative ability of pre-Industrial Era people to enjoy their own free time, for religious and or economic reasons is simply not feasible within today’s social and economic systems. Americans in particular have remarkably little paid time off, and our health insurance is directly linked to employment.

[NB. Of course, many historical people were not free at all, due to enslavement, indenture, or other terms of involuntary service. But the larger reality is that modern capitalism and its ubiquitous digitized international bonds define our daily lives. Even abroad, this is fundamentally something that limited others taking part in our journey, in a way in which free people in the past weren’t beholden.]

In conclusion: We are extremely lucky to be on this journey, through the grace of family and friends. But we are keenly aware that the modern liberties and amenities we enjoy in traveling are accompanied by structural limits which make us more reliant on said technology, and less supported by traditional systems of rural life, human-scaled transportation and a wider culture of pilgrimage.

Leave a comment